The Perils of Great Success

Most of the time, bringing an innovation to life doesn’t work out. But sometimes, in a magical moment, product-market fit is achieved, the market responds and there is a glorious period of success. But the thing we don’t talk about much is that this very period of success contains within it the seeds of future disappointment and even irrelevance.

The relationship between success and failure

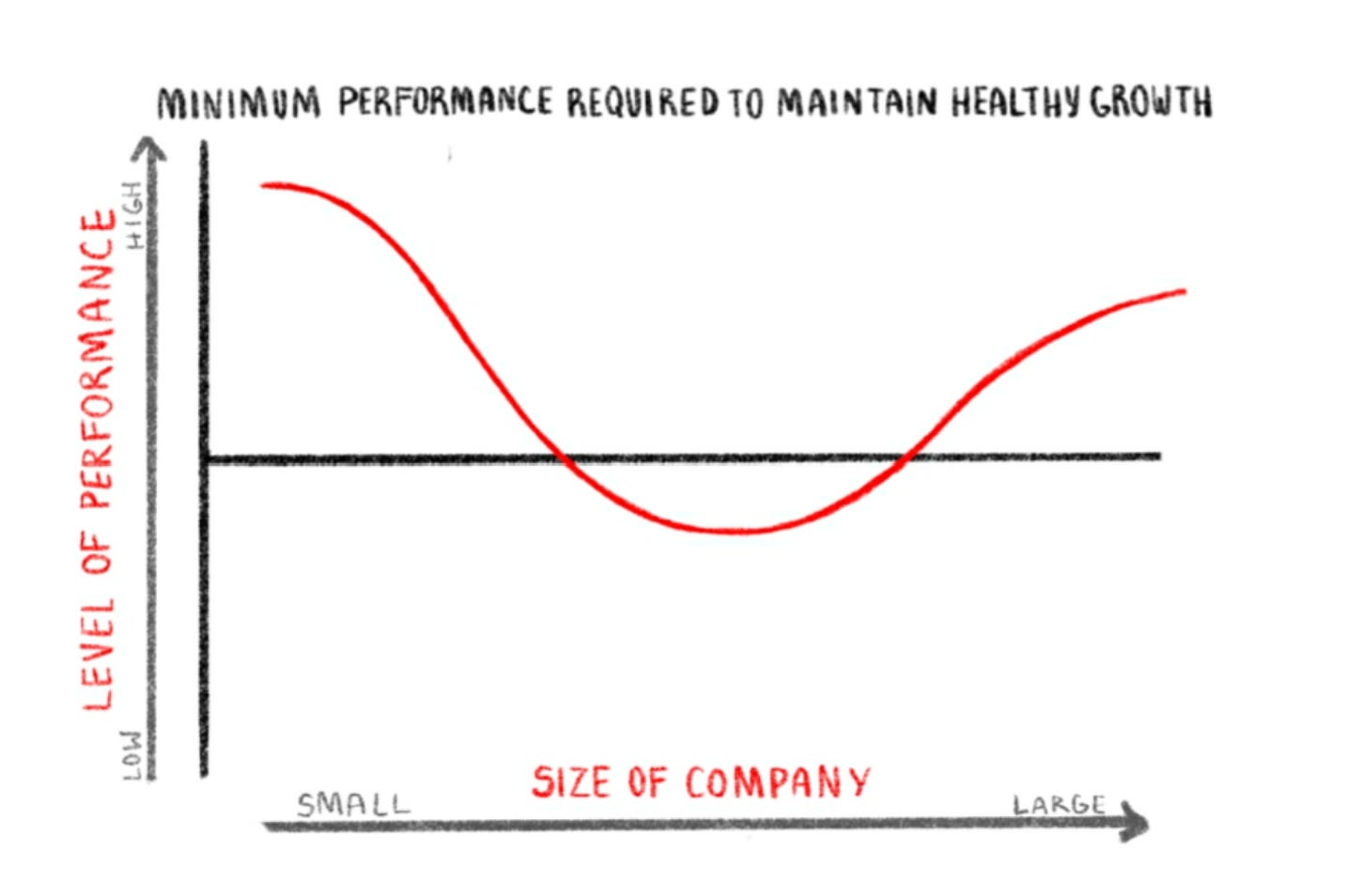

Jeff Severts, a corporate veteran and now innovator at the University of Chicago has an interesting stage model for the evolution of companies. In a business pamphlet (because he claims he hates business books), he suggests that companies go through four predictable stages as they evolve. His foundational model looks like this:

Here’s the problem as he identifies it: we think that performance is steady over the life cycle of a company. But in reality, there is a fascinating period where a company can let its performance slip, but due to a number of factors – momentum, inertia, the time required for competitors to copy and others – it can underperform but still keep its market dominance.

As Severts says, “… the minimum performance required to keep a company growing at a healthy pace varies as the company grows. When a company is small, it needs a very strong proposition to thrive. The same is true again when the firm is large. However, at a certain stage in a company’s life, a stage I call the Veil of Scale, a firm can lag the market with its proposition and still do quite well. (from Severts, Jeffrey. Deadly Memos: How Conventional Wisdom Kills Companies: Pamphlet #1 (p. 9). Kindle Edition).

Stage 1 of a company’s life is the startup stage. It’s hard. Most of the effort will result in failure. But if you get it right, it can be magical. Everything starts to work. Anything is possible! You’ve found an answer – extraordinary people (and for a startup to succeed, the people do need to be extraordinary) work together to change the world. It’s awesome!

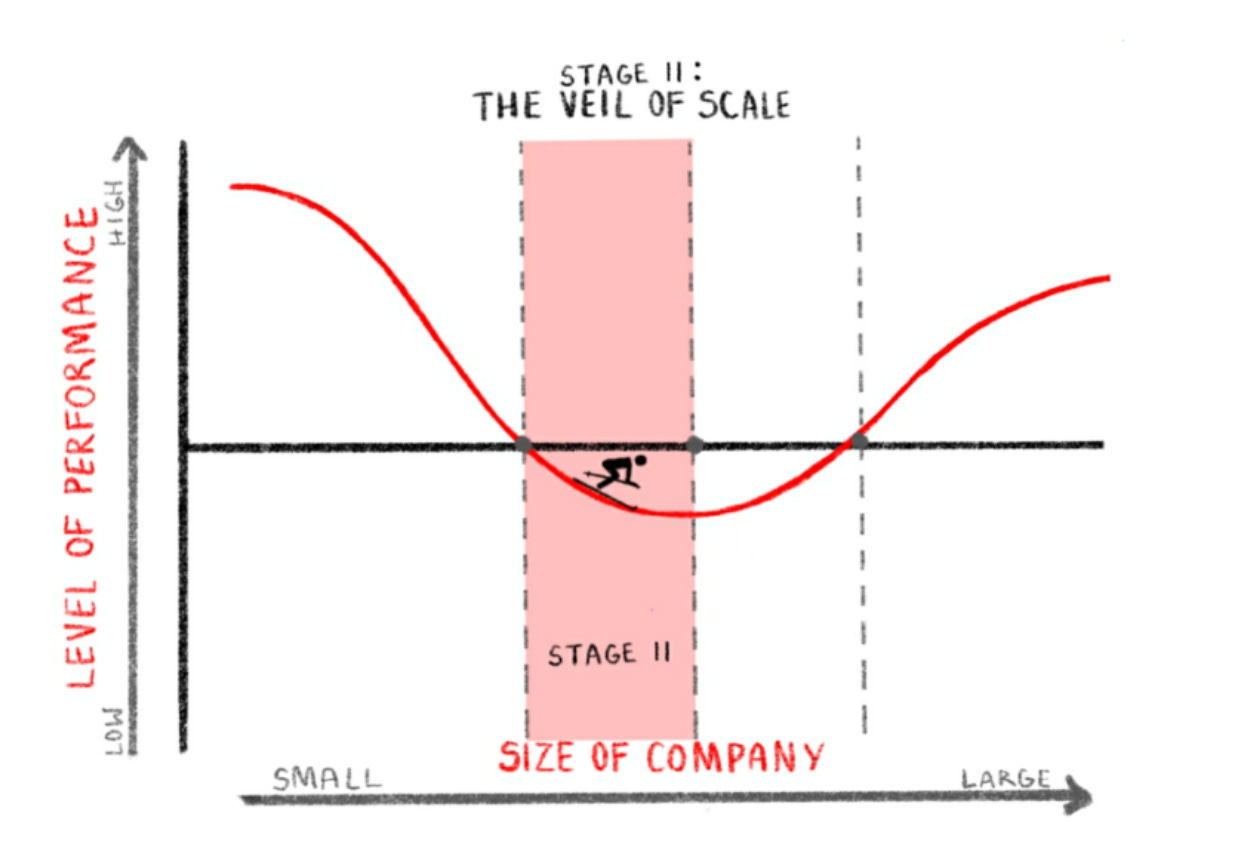

But then, as Severts points out, a growing company enters phase II, what he calls the “veil of scale.”

As he says, "This is when the Veil of Scale descends on a company, causing a form of mass delusion. Employees feel the thrill of skiing downhill, with sales and profit targets whizzing past them at high speed, often not realizing that the gravitational push of scale is subsidizing their results. This is a dangerous time because organizations will deceive themselves into thinking their success is deserved. Employees within the firm start to confuse cause and effect, believing that their presence, their work, and their decisions are better than they are. Confidence and power start to accumulate, reducing the quality of decision-making.

To make matters worse, the financial rewards to employees are typically growing rapidly during this stage. Bonuses are big and consistent. Equity stakes, if they exist, are becoming very valuable. Things are really good, and people now have a lot to lose. This reduces the incentives to innovate and take risks, two critical inputs for creating value. In short, the behaviors that created a company’s success now become rarer and go unrewarded.”

Then, the euphoric period comes to an end – it could be technological change, regulatory change, customer preferences shifting – any number of things. The company, now firmly centered on whatever caused it great success is suddenly faced with the punchbowl being taken away. This brings us to Severts’ phase III, which he calls the “scale flip.”

As he says, “Because, at this point, the benefits of being large have started to be outweighed by the costs. Decision rights are becoming unclear, with multiple groups expecting to advise or control every major initiative. Information is getting trapped in all the corners and crevices of the company, causing employees, especially those higher in the hierarchy, to make “stupid” (uninformed) decisions. And inertia is becoming the most formidable force – bad projects never die, good projects never get started, and the company’s old strategy horse continues to get flogged, despite plentiful evidence that it can no longer run. This extra friction inside the company makes everything harder, and it increases as the company grows. The only way to offset this burden is for the company to start improving its proposition to its customers, something it probably has not done since it was in Stage I.”

If the company can’t figure out how to build and move to the next advantage, it enters what is often a terminal stage of struggle, what Severts calls the “scale slog.”

As he says, “Getting anything done inside a Stage IV company is very difficult. The structural challenges that began to emerge in Stage III (e.g. unclear decision rights; poor information flows; inertia; etc.) are bad enough, but damage to the organization’s spirit is often the bigger problem. Employees have not experienced success of any kind in a long time. They grow pessimistic and avoid taking risks. They stop dreaming and creating. And because they cannot see a path out of this mess, they start looking for ways to capture and preserve a larger share of the shrinking pie for themselves. To overcome all this, a company must not only improve its proposition, but it must somehow get back to substantially outperforming its competition. This is very hard to do, so most Stage IV firms eventually die – or become the living dead.”

Another take on the same phenomenon, this time from Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs was once asked his view on why incredibly successful companies struggle so much to sustain their success once the initial wildly successful offering no longer can carry the firm. I thought his answer was fascinating and it points to a similar phenomenon that Severts observed (this was in the difficult period for Jobs after he had exited Apple and before his triumphant return in the late 1990’s):

Well, for PepsiCo, [having sales and marketing people in charge ] might have been okay. But it turns out the same thing can happen in technology companies that get monopolies like, oh, IBM and Xerox. If you were a product person at IBM, or Xerox… when you have a monopoly market share, the company is not any more successful if you make a better product. So, the people that can make the company more successful are sales and marketing people and they end up running the companies. The product people get driven out of decision-making forums. And the companies forget what it means to support the product genius that brought them to that monopolistic position in the first place…. And they really have no feeling in their hearts usually about wanting to really help the customers. So that's what happened at Xerox. The people at Xerox PARC used to call the people that ran Xerox toner heads. The toner heads would come out to Xerox PARC and they had no clue about what they were seeing.

As a company grows, the proportion of people involved in exploiting an existing advantage relative to the people engaged in either building a potential new advantage or transforming away from an exhausted one is likely to be much larger. Unless carefully managed, this can create a power imbalance in which the demands of exploitation completely overwhelm the need to build for the future.

Is this inevitable? No. Does it require skillful leadership? Yes.

In the work I’m doing for my new book, I’m finding these patterns of recurring success leading to failure to be more common than one might think, a reason that the average lifespan of a large company runs around 40 years. What is a solution? Adopting the new strategy playbook, making innovation a proficiency and adopting permissionless organizational forms. Not easy or natural, but entirely doable. This is among the challenges we work with companies to address.